how to get a return offer (and so much more)

20 months, 5 internships, 1 vacation / part 2 of 3

Out of my four five internships,

Before I go on, let me explain myself. If you recall (you probably don’t because it was so long ago…), when part one was published, the title of this series was 16 months, 4 internships, 1 vacation. Well, between part one and this post, I did a fifth internship and graduated college. A bit of time has passed, and the series title has been revised. Please forgive my tardiness. I found some time during this holiday season and decided the advice was still relevant, so here it is, my (late) Christmas gift to you. Back to the main content.

Out of my five internships, I received return offers for all three that were able to give them. Now, 6+ months after graduation, and I’ve just surpassed my first 90 days at…

None of them.

I didn’t expect to reject their offers. At every turn, I simply weighed my options and made whatever decision came out on top. At times, that was having a job at all; at other times, it was challenging myself in a specific role or technology; and at other other times, it was following my curiosity about an industry. Taking a results-oriented perspective though, it’s true that none of these internships materialized into anything post-graduation.

Now wait a minute, Marian. Isn’t that the point of an internship? To get a return offer? If you didn’t stick with any of them, what was the point of doing them at all?

Well, I’m glad you asked, Marian in italics. This article is for anyone who is stressed about getting a return offer, whether that’s due to your own performance or forces outside of your control (like, say, your company being bought out by a billionaire who is now the head of DoGE).

First of all, congratulations. Getting an internship is hard enough. Don’t add to your stress, and instead consider that an internship is worth so much more than a potential return offer.

And for everyone else, hey there and welcome. Maybe this wisdom can be applied elsewhere in your life, too.

I ended part 1 of this series on the remark that every internship presents a unique opportunity, one that quickly vanishes after university. Try telling a prospective employer that you would like a 12 week gig as a 0.5x (maybe even 0.3x) engineer with no professional experience and a lot of imposter syndrome. (Sorry, interns.) They won’t be pleased, but that’s the deal with internships—they’re scrappy, fraught with obstacles, and over before you know it, but that’s okay. For the employer, it’s not really about your output, and for you, it shouldn’t be about the return offer. The journey is just as important as the destination, and sometimes, as in this case, even more important.

Admittedly, my perspective has been shaped by the environment I did my internships in. The market was down, with hiring freezes and mass layoffs occurring left and right. I knew that despite my accomplishments, a return offer was not likely. In other words, my internship journey had no destination. Faced with this reality, I was forced to find a reason for my day-to-day work that wasn’t skipping the LeetCode grind and job security. (I heard a story recently about someone who heard that there were no return offers, and then proceeded to not show up to work. Ever. Not a single time after the announcement. He didn’t find his reason, but I respect it. He was just a chill guy.)

Now, for you, the environment is better-ish. But what if job security is still out of your control? If you get the internship, but not a return offer, did you fail?

This question was actually addressed during my internship at Twitter with one of the General Managers, Nick Caldwell, in a talk with the interns. He recognized our unfortunate situation. Months before we started our internships, we all thought they would be cancelled because of Elon. A few weeks in, it became clear that there was no future for us at Twitter. In this context, he explained that the one thing you can count on is yourself.

Your skills are your safety net.

With this perspective, let’s explore how to expand your safety net and make the most of your internship, despite not knowing what comes next.

your first two weeks

So you received your laptop in the mail, logged into your company email for the first time, and got a t-shirt with some abstract logo on the front. You’re ready to go — but wait, what do you “go” at?

The standard advice is to work through any mandatory onboarding videos and setup. Do it quickly (using Video Speed Controller, my favourite browser extension). Having said that, when you get tired of the 10th (or 2nd) onboarding video and your computer starts to sound like a jet engine while installing apps and cloning repositories, there are more subtle, optional things you ought to do.

one-on-ones

A one-on-one is a simple, 30-minute-to-an-hour chat between you and another person. One of the best things to do in your first two weeks while you are still getting familiar with the codebase, your project, and your team members, is to make that last part more personal. Take initiative to set up one-on-ones with your teammates. You’re going to work with these people for the next couple months, and that’s a lot easier to do when you know more about them than their first name, three fun facts, and a Slack handle. Of course, be mindful of their time and ask before sending an invite.

In your meetings, you can get started by asking basic questions like:

How long have you been working here?

Why did you join?

What do you work on?

But don’t shy away from non-work-related questions, such as:

What do you do in your free time?

Where did you grow up?

What was your favourite course in university?

It may sound daunting to set up so many meetings, but it’s a great way to get comfortable in your new role and break up the monotony of onboarding. People also tend to be more open and friendly towards new hires, especially interns, so there’s no need to be nervous. Clear communication is essential to being a software engineer, and that’s a lot easier to do when you know the people you have to communicate with. So, dispel any notions you have about “code monkey” software engineers who speak to no one and type furiously all day in their cubicles. They’re false and won’t get you very far.

shadow a team member

Every person has a distinct workflow. They use varying technologies, shortcuts, and processes, and when you’re a newcomer, you might be familiar with one, but certainly not all of these.

At my first internship, before my first commit or ticket, I made it a point to ask a team member to walk me through their current project/task. By doing this, I gained insight into their workflow. I was able to answer questions such as:

What IDE/text editor do they use and why? What other tools do they use frequently?

How do they navigate the repository? What shortcuts are they using and what are they looking for? What is the folder structure and what does testing look like?

How does the team use Git? Are there any conventions for commits, merging, and the like?

This was so helpful that I proceeded to do it, formally and informally, at all my subsequent internships.

In your first two weeks, prioritize doing these two things. And for the next ten, I’ll leave you with just three more.

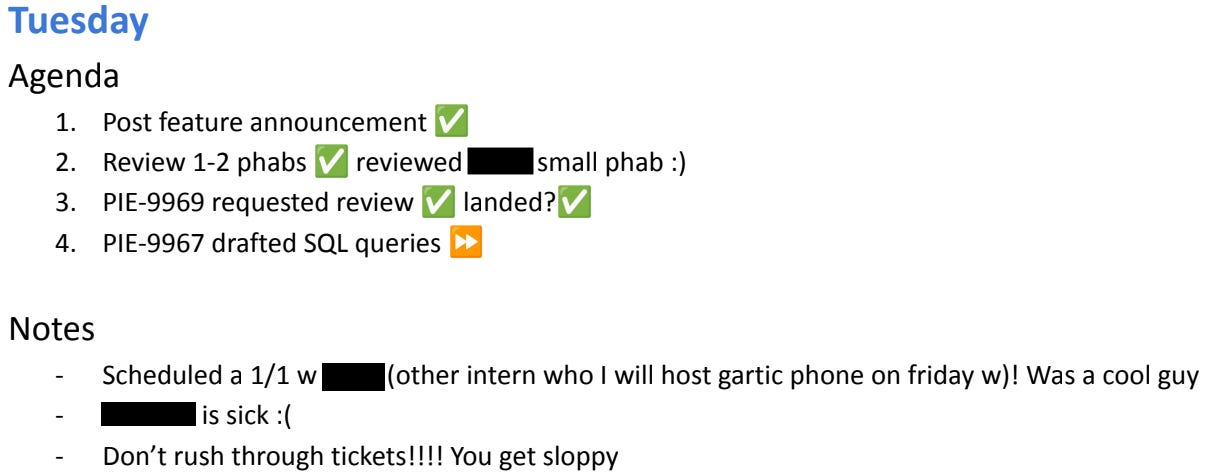

1. keep weekly summaries

This was by far the best tip I ever received1. An intern lives a busy life. We have to onboard, gain context, network with coworkers, complete a project, make time for intern buddies, and then offboard and handoff all of our work in 12 weeks, no extensions. It sounds like a lot of time at first, but roadblocks inevitably arise that cause the work to progress slower while the weeks pass by faster.

In this rush, being organized is of utmost importance. In your weekly summaries, you’ll have a place to save the links you knew would be useful at some point, or that small command your team member told you to run before your next commit, or a heartfelt message you received from a mentor that would otherwise be lost to Slack within the hour. On a more practical note, these summaries will help you remember what you accomplished when compiling your internship presentation (or going for promotions and bonuses as a full-time employee).

If you remember one thing, remember that you are worse at remembering than you think. So write it down.

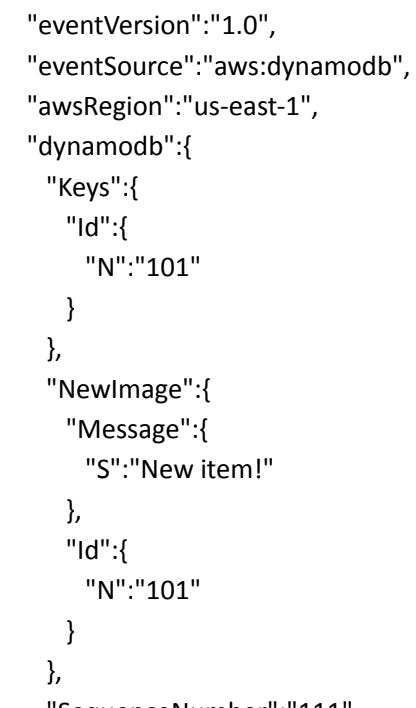

You’re the only person that will see this document in its raw form, so structure it however you like. What worked for me was having a to-do list each day, as well as a notes section. My notes section would contain an amalgamation of screenshots, copy pastes, acronym definitions, events, and thoughts.

I would recommend making it digital so you can save links and do stuff like this ⬇️

More than just a recollection and history, these weekly summaries also served as a source of encouragement. On days where I was burnt out and spiraled into pessimistic, self-deprecating thoughts, sometimes failing to recall what I did just a few days prior, I would read and realize that I was always working and making progress on something. Each entry was a reminder that I was constantly learning, which fueled my productivity and focus.

2. the biggest hurdle: asking questions

If you find your summaries aren’t filled with learnings, you might not be asking enough questions. Overcoming the hesitation to ask questions is a common hurdle for interns, but not for you, eager beaver. Since you’re reading this post, you’re ahead of the game and well on your way to becoming a super curious, outspoken, uncommon intern.

Personally, my biggest fear was looking stupid for not knowing the answer. What a defeating mindset! No one worth learning from would think that. Luckily, there’s an extremely easy way to eliminate this doubt:

Research, then ask.

Doing your due diligence will assuage any doubts about it being a stupid question, while also showing respect to the person you want to ask — you respect their time, so try to solve it on your own first.

Once you’ve decided that you will ask, then, when you ask, make sure to provide ample context. A good template here is:

I’m working on X trying to do Y, but stuck on Z. I have tried W.

This template includes both the current context and prior research that you’ve done. It saves the answering party from asking “What have you tried?” or “What are you trying to do?” which means there will be less back-and-forth required (this can be really slow when messaging online), and you will get answers faster. Hooray!

how to ask questions

In case it’s helpful, here is my usual question-asking workflow:

Ask Google. Or ChatGPT, if you trust it.

Search in Slack, or whatever internal communication your company uses.

If you’re blocked during dev setup, there’s a good chance someone has been in your shoes before. You can often copy paste your error message (just the important bits) and find someone else who was encountering the exact same error, and a solution that worked for them. This has saved me multiple times.

Look through the documentation. Engineers love documentation. This is probably on Confluence or something similar.

Finally, ask in the most relevant channel. This could be a broad channel, directed at multiple people, or a single person.

If the conversation starts to become a discussion, it might be better to huddle instead2.

Asking questions allows you to unblock yourself as quickly as possible. You might learn something by spending hours trying to figure it out yourself, but if you could’ve learned from someone else in a matter of minutes, then you wasted both your own and your team’s time. Be humble and teachable.

3. use tools

My final tip is to sharpen those knives of yours. By knives, I mean fingers. And by fingers, I mean brain. Sharpen your brain by learning the tools needed for the job. As a software engineer, two of our most important tools are git and keyboard shortcuts.

learn source control (git)

During my first internship, I must have spent as much time writing the code as I did trying to merge it. If you’re lucky, you’re taught how to use git in school beyond the basic add, commit, and merge commands. If you’re like me, you could never quite figure out which one was the current versus incoming change in a merge conflict.

If you’re going to do one thing before you start your internship, learn how to use git well. In my experience, different companies choose to use git differently. Some prefer more structure, where each commit is reversible and encapsulates a singular idea, whereas some are fine with commit messages like “typo”, “trying again”, or “nit” because it all gets squashed in the end. You should know how to do both.

The commands I use most often are listed below. I use Oh My Zsh to manage my terminal, so most of these commands are shortened to three-ish keystrokes thanks to the git aliases which are listed along with their full command counterparts. (I know you didn’t ask, but my personal favourite is glola and you should try it.)

git checkout <branch name>gcogcb

git addga .

git commitwith and without the --amend flag

gc -m “message”gc!

git rebase -i HEAD~<number of commits backwards>When I learned how to do this, it changed my workflow and made it feel so much cleaner.

grb -i HEAD~<number of commits backwards>

git pushwith and without

--force origin $(current_branch)gpsupggf

git reflog

I learned most about git while working, but a previous manager recommended an interactive online tutorial (Learn Git Branching) which seems like a good place to start.

learn shortcuts

Think of an oil painter. They know how to vary the brush, technique, and paints as they move from the underpainting (initial layer) to details and glaze. Their job is to manipulate paint, and they have mastered how to do so efficiently.

You shouldn’t treat software engineering any differently. We’re not oil painters, but we're still artists (and that’s why AI won’t replace us just yet…). Our job is to manipulate text, and we should be learning the best ways to do so.

There are so many different text editors out there, so I’m not going to suggest any one to pick—as long as you pick one and learn it well.

The shortcuts I find myself using most often are:

Multi-cursor editing

Find and replace symbol/word

Follow and find references to a variable/function

Search and navigate to a file

As a general rule of thumb, once I notice myself performing an action at least three times, I’ll look up the keyboard shortcut or define one myself. I’m currently learning neovim so I can have more customization and keep my fingers on the keyboard as much as possible.

closing thoughts

Just like part 1 of this series, I wrote this because I wish I had something like it when I was looking for and starting my internships. These are the practices that worked; they are the ones that stuck across five internships in two years, and through the first 90 days of my first full-time job. If you found it helpful, please consider buying me a coffee to support my writing.

Or, if you’re a coffee addict like me, let’s set up a coffee chat!

Until next time, which will be the final part of this series. I’ll be reflecting on my time at Twitter, Amazon, Brilliant.tech, Khan Academy, and Arc Boats.

Subscribe to get it in your inbox and thanks for reading.

Huddling is a Slack-specific term that I love, but the idea is just to hop on a quick call with a team member who can help you. Some technical discussions are much easier to have over voice. It’s also helpful to document the conclusion in writing by sending a message prefaced with something like “Discussed offline and decided…”.

Given that I’ve kept some type of daily journal for the last 10 years, it’s strange that I didn’t think about doing that in the context of work. Thank goodness for people who see things about yourself that you miss.

Using these tips to start the new year in my new-ish full time job!

so cool! found you on my feed — enjoyed reading :)